A Brief Book Summary from Books At a Glance

Author Notes

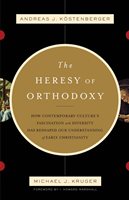

Andreas J. Köstenberger is senior professor of New Testament at Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary and a prolific author. Michael J. Kruger is President and professor of New Testament at Reformed Theological Seminary. He is the author of a number of articles and books on early Christianity.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Part 1: The Heresy of Orthodoxy: Pluralism and the Origin of the New Testament

1. The Bauer-Ehrman Thesis: Its Origins and Influence

2. Unity and Plurality: How Diverse was Early Christianity?

3. Heresy in the New Testament: How Early was It?

Part 2: Picking the Books: Tracing the Development of the New Testament Canon

4. Starting in the Right Place: The Meaning of Canon in Early Christianity

5. Interpreting the Historical Evidence: The Emerging Canon in Early Christianity

6. Establishing the Boundaries: Apocryphal Books and the Limits of the Canon

Part 3: Changing the Story: Manuscripts, Scribes, and Textual Transmission

7. Keepers of the Text: Were Texts Copied and Circulated in the Ancient World?

8. Tampering with the Text: Was the New Testament Text Changed Along the Way?

Concluding Appeal

Summary

Chapter One:

The Bauer-Ehrman Thesis: Its Origins and Influence

The German Theologian Walter Bauer, born in 1877, first disseminated the idea that the earliest forms of Christianity were not answerable to any authoritative tradition and developed in diverse and uncontrolled ways in his book Orthodoxy and Heresy in Earliest Christianity. Bauer backed up this claim with what he took to be early historical signs of relative diversity in Asia Minor, Rome, and Egypt. The influential New Treatment scholar Rudolf Bultmann picked up Bauer’s thesis and used it to justify his de-mythologizing hermeneutic, positing existential faith as the only essential creed uniting all diverse forms of early Christianity. James D.G. Dunn pushed the Bauer Thesis further back, emphasizing the conflicting diversity of theologies within the New Testament itself. In more recent times, the Bauer thesis has entered the mainstream consciousness through the popular scholarship of Elaine Pagels and Bart Ehrman. The practical implication of Bauer’s thesis, as his popularizers emphasize, is that we must “move beyond dogmatic notions of orthodoxy and instead embrace a diversity of equally legitimate beliefs.”

From its first publication, Bauer’s thesis has not gone unchallenged and the authors summarize some of the major criticisms that have been leveled against it. For one thing, the thesis proves too much. It only demonstrates that there was diversity early on, but not that such diversity was the product of equally legitimate claims to authority. For another, Bauer takes an unwarranted narrow view of the ways in which a diversity of expression and emphasis can be accommodated within an overall coherent and consistent system of belief, such as orthodoxy. Finally, Bauer’s historical evidence is sketchy and can be interpreted in different ways to reveal the resiliency of the beliefs later identified as orthodox and the tenuousness of heretical beliefs wherever they were held. It is particularly the criticism of Bauer’s historical evidence that the authors develop in the following chapters.

Chapter Two:

Unity and Plurality: How Diverse was Early Christianity?

In answering this question, the authors first address Bauer’s original historical arguments before turning to Bart Ehrman’s more recent reincarnations. The authors systematically look at the evidence Bauer adduced from early sources in Asia Minor, Egypt, Edessa, and Rome to suggest that heresy was first on the scene before orthodoxy. On closer analysis it becomes painfully obvious how much conjecture and assumptions Bauer must make in his own favor with the scant literary evidence we have. Beyond this, Bauer is far too demanding, defining texts as Gnostic or heretical which are more or less in line with an orthodox view. Other heresies, like Marcionism which may have reached Edessa first, could only arise where orthodox notions already made sense. Finally, Bauer’s claim that Rome developed and enforced orthodoxy on the rest of the Christian world…

[To continue reading this summary, please see below....]The remainder of this article is premium content. Become a member to continue reading.

Already have an account? Sign In