It’s a topic relatively few Christians across the centuries have been asked to address, but it’s one of the leading issues of our day. God and the Transgender Debate.

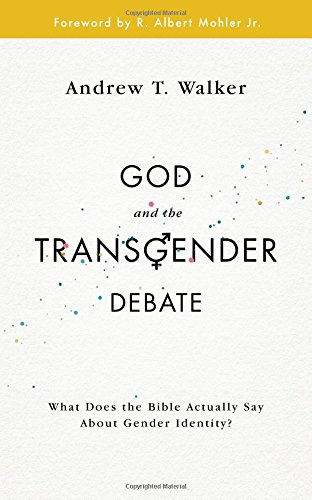

I’m Fred Zaspel with Books At a Glance, and we’re talking today to Andrew Walker, author of the book by that title – God and the Transgender Debate, new from the Good Book Company.

Andrew, Welcome. Congratulations on your new book, and thanks for talking to us about it.

Andrew Walker:

Hey, Fred, thanks for having me on and I appreciate the opportunity.

Zaspel:

On one level it may seem pretty obvious, but you devote the majority of your first chapter to the question: Why this book? And why now?

Walker:

There’s a very pragmatic answer to that. First off is the fact that there’s very few resources out there. There’s a couple of books that exist, one that’s very, very small by Vaughan Roberts, which I recommend but that is very, very small; and then there’s a longer volume that’s much more academic by Mark Yarhouse that I don’t think will be read by Christians in the pews, it’s more for specialists. And, quite frankly, there are problematic aspects to Dr. Yarhouse’s work that I can’t recommend to others, strongly. So there is a void on this issue and this is an issue that I care about because for the past, I would say, five years in my career I’ve really had this issue or concern about this issue of biblical anthropology, this understanding of what it means to be a man or woman made in the image of God and what the ramifications and consequences are to how God made us. And I would actually make the argument that most of the current controversies we’re having today in Western civilization are having to do with these anthropological questions. The life issue, for example, on abortion is a question of anthropology – is unborn life, life? Issues of euthanasia that we’re seeing happen across and growing across Western civilization is this issue of what does it mean to be a dignified human person even amidst suffering, and the prospect of death, and how we treat people in light of that. And so we are having a lot of these anthropological questions.

And then there’s this issue of transgenderism which I think is actually a foundational frontier issue on theological anthropology. Because if we can’t get the question of what does it mean to be a man or a woman correct, we’re going to do a great disservice in trying to cast any broader normative picture for what we think churches and society ought to believe about the nature of humanity. So, again, there is a pragmatic issue – there’s just nothing out there, a theological issue – we have got to get this right because there’s human flourishing at stake and what the Bible teaches about anthropology, especially being made male and female. This is not a sectarian ethic, this is a universal, creational ethic, and we need to get this right for the sake of the church’s social witness, but also how we love our neighbor.

Zaspel:

Define some terms for us: sex, gender, gender identity, gender dysphoria, and transgender. And with that maybe you can give us a brief overview of your book, so readers can know what to expect.

Walker:

Sex just refers to the biological characteristics that we associate with personhood. So, if you’re a man, you have XY chromosomes, if you’re a female you have XX chromosomes. That difference manifests itself in our reproductive capacities, in our anatomical capacities, our physiological capacities. And so, sex refers to the embodied and nature of humanity.

Gender is what I would say is the social expression of biological sex. It has always been the case that gender is always followed from sex in whatever kind of culture we live in. The example I always give is in 13th-century Scotland a guy like William Wallace, which is from my favorite movie, Braveheart, it was appropriate for men to wear kilts because that was something that was associated with masculinity. And that’s something that we would not associate in 21st century America. So that means that gender does change from one culture to the next as far as the expectations around gender, but it’s always been understood that gender follows from sex. It’s kind of the cultural association that we have with sex.

Gender identity is kind of a contested term but it’s generally the sense and how people view themselves, male or female, psychologically. It’s an internal self-perception of how they sense themselves being male or female.

Gender dysphoria is this phenomenon where people experience a conflict or stress at a perceived misalignment between their biological sex and their sense of gender identity. So, what I mean by that is that you have individuals who are born XY chromosome, that’s a male, but who might at the psychological level sense themselves to be a female. And so, gender dysphoria is the sense of stress at that perceived misalignment or incongruence. And it’s important, at this point, to say that not everyone who experiences gender dysphoria is going to necessarily identify as transgender, and I’ll explain that word now, too.

Transgenderism is what I would say is a much more comprehensive social political cultural identity where someone who experiences that misalignment and incongruence is then taking steps to live and express themselves in accordance with their perceived gender identity. So, you no longer identify with your biological sex, but you identify with your gender identity. So that means people will take on a new name, new pronoun, a new style of dress and maybe even take hormones and have surgery to try to live in accordance with their sense of gender identity.

I appreciate the idea of the words here because the vocabulary really, really matters and the language really, really matters. But, as far as the overall book, if I can give a real short snippet, the book is meant to address the issue from every relevant angle that I think Christians need to be thinking through this. That’s understanding how we got here as a culture; it’s understanding kind of an introduction to a biblical creational ethic of male and female, so a theology of the body, so to speak. And then there’s a discipleship component. So, what does the Bible expect of those who grapple with gender dysphoria and what does the Bible mean for those who identify as transgender but are repentant and want to express faith in Christ, and what does the Bible mean then? And then, finally, there’s also a call to the church and a call to Christians as far as how we love and engage this issue practically at the local level. And then at the very end there’s a Q & A section about thorny issues that Christians might find themselves in the culture, about pronoun usage, about bathroom bills, and about how to talk about this with children, for example.

Zaspel:

Sex and gender – isn’t the one necessarily tied to the other?

Walker:

I would say, yes. And as I said a second ago, gender has always been the cultural association that we attach to biological sex. For example, in Western society, blue has been denoted as a way to communicate masculinity for a child at birth and pink for a female at birth. There’s nothing intrinsic to blue or pink that makes those either male or female, but society has decided to attach those colors to the meaning of sex. Again, there’s this principle that gender is always followed from sex. What’s going on right now, is we’re seeing a new experiment where gender is completely severed from sex altogether. Therefore, you can identify with the cultural associations of gender at the expense and neglect of your biological sex. And so that’s the radical kind of innovation aspect to the transgender debate.

Zaspel:

You emphasize that men and women are equal but different. On one level that seems pretty obvious, but what are you getting at here? And how is this important with regard to creation?

Walker:

I am really adamant in the book about wanting to develop a creational kind of theology of the body type ethic where individuals understand that we are created beings. And this Creator/creature distinction is fundamental to biblical anthropology. Understanding that we are created beings, which means we aren’t self-sovereigns. We are not simply autonomous beings whose highest fulfillment is to express our will. Our highest fulfillment is to live in accordance with the nature God has given male and female. And so, what I’ve tried to argue for in the book is that there is an ontological equality between male and female in the sense that male is no better than female and female is no better than male; but that creational difference has manifested itself down to the level of our chromosomes, so that we are not just homogenous blobs; that we actually are separate beings. I marvel at the fact that in creating humanity, God made humanity in two halves and that’s the male/female form. So, you think about the difference being knit down to the level of our chromosomes, which to me, sends the signal that there is an essential difference in our created nature. And so, what is incumbent upon us as created beings is to live in accordance with that createdness and that difference and not to try to suppress it or nullify it. Which I would actually argue is futile. That someone who is identifying as transgender, who might think that they are a female when they are biologically a male, there is no sense in which they truly are female. And that’s where there is a philosophical component to this debate. The culture is asking us to accept the philosophical premise that a man who identifies as a woman can be a woman. And we simply cannot abide that, because it’s biologically false, it’s philosophically false, and I think biblically and theologically, it’s heresy.

Zaspel:

What does worldview have to do with all this? How has a changing worldview brought us to where we are now on this issue, and how are these questions settled?

Walker:

The worldview issue is paramount. It’s the presuppositional component to the transgender debate and that’s these questions of who am I? Why am I here? Who am I accountable to? What is right and wrong? What is my ultimate destiny? And so, we are going to address these questions of gender and identity and our bodies through some prism of a worldview. And what I would want to challenge those on the transgender debate is to test whether or not the worldview that they are holding is consistent on these issues. For example, I saw a commercial around Mother’s Day where Dove soap had an advertising campaign where a man who thought that he was a woman was identifying himself as a mother. And it was very “social justicey,” very tolerant and diverse was the theme. But it’s very pernicious, that teaching, because it sends the signal that if a man can identify as a mother, we’re actually nullifying a true concept of motherhood. Because we’re saying that biological mothers are really no different than men who think of themselves as mothers. So, we do damage to the mothering enterprise for the sake of social justice, or I would say a progressive vision for social justice. There’s just an inconsistent ethic, but that inconsistent ethic is born of what I would say is an irrational worldview. To me, this boils down to an examination of presuppositions about where we are going to be willing to take our principles to their logical conclusion. And I just think the progressive and secular ethic on this is unsustainable.

Zaspel:

You make the point that the confusion of gender roles is not a Christian option – in fact, that it is a rejection of Jesus. Explain that for us.

Walker:

We often hear the phrase that Jesus is completely irrelevant to the same-sex marriage debate and the gender debates because he just never talks about it. Which is absolutely false. There are no statements where Jesus says “thou shalt not be transgender,” or “thou shalt not be in a same-sex marriage.” But what does Jesus do in Matthew 19? In Matthew 19 he says, “Have you not heard? From the beginning he made them male and female.” Jesus is taking the creational ethic of Genesis 1 and 2, and reaffirming the ongoing validity of that framework, even in a fallen world. So, Jesus does weigh in on what marriage is and what human embodiment means because he is reaffirming – he is in essence ratifying this creational paradigm that we see at the very opening pages of the Bible. So Jesus’s words are very, very relevant here.

Zaspel:

In what sense is Adam and Eve’s story our story?

Walker:

Great question. Adam and Eve are embodied human beings who rebel and there is a consequence to that. What I write about in the book, and I want to be careful with in arguing, is when they sin, there is disobedience, there is a casting off of the Creator/creature distinction, but interestingly, what we noticed in the early pages of Genesis is that there is an awareness of their nakedness, and there is an embarrassment at it. And so there is, for the first time, as the result of living in a sinful world, there is some type of disconnect at the psychological level between themselves and how they are experiencing their bodies. Now, I’m not saying that it’s gender dysphoria. Please hear me be clear on that. But what I am saying is that there is some type of bodily alienation from our psychological sense of perception at the very introductory stages of sin. So, there is something about our bodies that bears witness to living in a broken creation. Only a broken creation would tell us that our bodies are something for us to be embarrassed about. And so, in that sense, Adam and Eve do offer a paradigm for living in a broken and fallen world where there is a sense of alienation between body and self.

That story then repeats itself all through the rest of humanity until we find the new human in Jesus Christ, the true humanity. Ultimately, we are patterned after the image of God; Adam and Eve bear the image imperfectly; we enter that imperfect image, but the pathway of biblical theology is to be renewed in the image of Christ, because Christ is the image of God. And so, from the storyline of Scripture we see how we once were created to be, how we fell into sin, and how we live in a world where not all things are as they once were. But we also look to the future which means that we are on a path towards a future of how things will someday be but how they currently are not right now. And so the Bible, to me, offers this terrific, panoramic landscape and narrative of how to understand the transgender debate from Creation, Fall, redemption, restoration.

Zaspel:

Talk to us about the “I was born that way” argument. You point out that whether the claim is true or not, it is not a clinching argument. Why?

Walker:

Certainly not from a biblical worldview. This idea that “I was born that way,” assumes that a fallen, deceived heart, which also results in a fallen, deceived mind, that that’s normative and, therefore, whatever we experience innately and intrinsically is something to be nursed and accepted and welcomed. And that’s simply not a biblical anthropology. And, moreover, secular society doesn’t really believe that. We all have feelings of lust, we have feelings of envy and greed and covetousness and hatred. We would all say, even secularists would say, that just because you feel a sense of hatred and that you were born with that sense of hatred, that’s not something to be nursed and to be embraced and affirmed. So, again, we are back again at the level of worldview and consistency in worldview and asking the question of who has a consistent worldview. Because it’s not consistent to affirm covetousness and hatred inside the heart, but the Bible does have a way to diagnose that. It’s to say, yes, that’s because we’re fallen and we are sinful and we need redemption from sin. But we can also look at Genesis 1 and 2 as the normative description of what humanity was designed to be, but then also looking again to the path of sanctification and redemption that we see at the end of the Bible and know that we are striving toward something even living in a broken creation.

Zaspel:

You emphasize that Christians must remember our Lord’s command to love our neighbor. How might that apply here? What does that look like in reference to, say, a neighbor or work associate who is transgender?

Walker:

The challenge here is not to make the transgender issue supremely different than how we would just do neighbor love and practice neighbor love on any other issue. This is issues of basic respect, decency, kindness, empathy, a sense of being willing to regard someone we disagree with as a full, ontological image bearer of God. And so that even someone we disagree with is deserving of respect and kindness and a sense of dignity. But it also means, too, that we want to be truthful; and that means we want to be willing to share our convictions, kindly, but to share them at least. I think, too, what does make this particularly unique is that this is an issue where the vast majority of citizens will never experience. And so, when someone comes into your world either experiencing gender dysphoria or transgender there is a sense in which we do need to be extra cautious and be willing to extend an extra level of empathy and patience because there is a lot of psychological and mental health issues at stake here. So, we want to be extra kind and extra loving because, again, I really want to emphasize, there are tremendous psychological issues at stake in these individuals; and just out of Christian love we want to be kind to them.

Zaspel:

What is the challenge you want to give to the church?

Walker:

Oh, goodness! I’ll condense that down to something very simple because I could go on for an hour about that.

The challenge to the church, I would say, is to stand courageously and joyfully on the Word of God, knowing that it is sufficient and true and good for us as humans and it’s relevant to the world around us. And so, from that it means that we are going to have to strip away the trite, easy answers and be willing to do some hard work and some serious intellectual investigation, because so much of these conversations that we are having is stripping away what used to be tacit, implied categories in society. So we’re going to have to do some hard work. What that means is, to have some hard conversations and do some serious reading.

But I also think it’s a call to arms; it’s a call to joyfully proclaim the truth of how God made us to a dying world that is content to live in its own mess. And not to just reject the world as hell-bound and is a lost cause. But to understand that a part of the gospel message is its creational repercussions, that God is promising to renew the cosmos in the person of Jesus Christ., and so that physical matter actually matters. So, in some mysterious way, the redemption of human souls is inseparable from the redemption that is going to be experienced in encapsulating the rest of creation around us.

Zaspel:

In chapters 11 and 12 you offer some counsel to parents on talking to their children and other “tough questions” Christians may face. We can’t get into these now, but I think our listeners will want to be aware of the kinds of questions you address here.

Walker:

The first thing (I’ll keep it really simple on the kids’ issue) is, first, be willing to have the conversation with your kids. Because if you don’t have the conversation, the culture will be more than happy to do that. Parents do not have the luxury of sitting on the sidelines on this issue; they actually have to have the conversation. It doesn’t mean they have to be experts; but, it does mean that if they are asked the questions, they need to be equipped to find the resources to answer the questions. And it’s okay not to know all the answers. We want to give parents that affirmation. But it does mean that they are going to have to do some hard work. So, have the questions with your kids. And I would say have the questions preemptively with your children and don’t wait for your child to come with those questions to you. The second thing I would say is to have these conversations age-appropriately. It doesn’t mean at the age of 3 ½ you’re overwhelming your kids with phrases like gender dysphoria, but you are having implicit conversations where you’re affirming the goodness of your child’s maleness or femaleness. And saying, “listen, isn’t it wonderful how God made you a boy or a girl.” Just affirming basic categories like that.

As far as the tough questions – I talk about can someone be transgender and a Christian? Which has generated a lot of conversation. I talk about what’s going on in public schools and how parents should think through that issue and be prepared. What to do in a local church if church elders or a congregation is asked by a parent to identify a child by a different pronoun than their biological sex. I talk about the bathroom policies and how that’s something parents want to pay attention to. Laws – as far as nondiscrimination policy and how that might affect churches. The issue of hormones and how that is affecting our children. And then this “harm” principle of, if you believe in the Christian ethic, is that innately harmful for transgender persons? There’s a few other questions, but that gives you a taste of what I’m trying to do in those chapters.

Zaspel:

We’re talking to Andrew Walker about his new book, God and the Transgender Debate. It’s an important contemporary question, and we encourage you to pick up this book for help with some answers.

Andrew, thanks much for your good work, and thanks for talking to us today.

Walker:

Thank you, Fred.