A Book Review from Books At a Glance

by Jacob C. Boyd

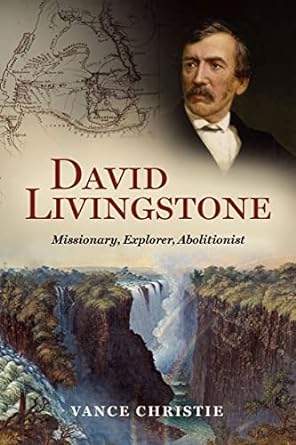

Vance Christie achieved a monumental task in giving an account of David Livingstone’s life by carefully analyzing the vast information found in journals, letters, and other primary sources. As Christie tells the story of Livingstone’s life, he seeks to give him a fair evaluation in light of the strong criticism he has received throughout the years after his death. Three main areas of criticism Livingstone has received that Christie addresses throughout the book include: his comments about the physical appearance and abilities of Africans, his long separation from his family, and his desire to establish British colonies in Africa (15). While seeking to treat Livingstone fairly, in light of the standards during his day, Christie aims to “chiefly focus on the important events of his personal history and on the three primary emphases of his career as a missionary, explorer and slave trade opponent” (15).

Christie divides the book into four sequential sections, consisting of 62 chapters in total. Part one covers Livingstone’s birth in 1813 through his early missionary career in 1849. This early biographical sketch tells of Livingstone’s medical training, his youthful missionary aspirations, his marriage to Mary Moffat on January 2, 1845, and his first covert, Sechele, in 1848. Part two gives a detailed account of Livingstone’s expansive missionary travels, from May 1849-July 1857. This second section is where Christie primarily considers Livingstone’s missionary career, ending when he arrives back to Britain to reunite with his family after four and a half years away from his family on 16 years since initially left London (341). It was during this he wrote his book Missionary Travels. Part 3 begins after Livingstone resigns from the London Missionary Society in 1857 and is commissioned by the government as the leader of the Zambesi Expedition to explore new routes in and through Africa. This section covers his career as an explorer from August 1857 to December 1864. This time is marked by interpersonal conflicts with others on the expedition such as the controversial dismissal of Baines from the expedition in 1859 (429-440). During this time Livingstone begins to have run-ins with slave traders and begins to work against them. This phase of Livingstone’s life ends when he again returns to Britain in 1864. Part 4 begins when a man named Murchison proposes to Livingstone to help fight against slavery as a surveyor, which consists of the final nine years of his life. By the end of Livingstone’s life, the East African slave trade was coming to an end. Christie notes, “That public opinion [against the slave trade] has come about largely due to Livingstone’s tireless efforts to expose the evils of that trade which he witnessed while traveling throughout the south-eastern interior of the continent” (745). Livingstone died on May 1, 1873.

Throughout these three different phases of Livingstone’s career, Christie does a great job at considering the three specific critiques listed above that many had thrown at Livingstone. There are times when Livingstone writes questionable things in his journal when commenting about the physical appearance and abilities of Africans. For example, on May 20, 1855, Livingstone wrote, “There seems an utter hopelessness in many cases of the [African] interior, except by a long-continued discipline and contact with superior races by commerce” (293). Livingstone explains they are helpless because of their “inured to bloodshed and murder, and care for no god except being bewitched desire of fame by killing people of other tribes…” (293). Christie does a good job of interacting with Livingstone’s choice of words when he says, “superior races,” in order to give Livingstone a fair critique. Christie explains, “It is important to note that he did not think some races were inherently superior to others. Rather, he believed that some races, from a variety of both Divine and human causes, had attained superior accomplishments and blessings in terms of religion, civilization, education, industry, technology, commerce and the like than had other races” (293).

As early as 1852, Livingstone spent extended time away from family. Christie points out that “missionaries and mission societies in that era commonly viewed such family sacrifices as necessary and legitimate for achieving their ministry objectives” (199). Christie goes on to share a support correspondence letter by Tidman, one of the London Missionary Society directors, toward this end. Tidmon wrote, “We have given our best consideration to your proposal to send Mrs. Livingstone and your children to this country for a season, in order that you may be left entire liberty for the space of say two years to prosecute your investigations in the regions that have been laid open to you” (199). As mentioned above, this time away lasted four and a half years instead of two, as suggested in Tidmon’s correspondence with Livingstone. Livingstone and Mrs. Livingstone also spent a considerable amount of time away from each other during the Zambesi Expedition and the time he worked as a Surveyor, while the older kids stayed in Britain for their education.

At the beginning of Livingstone’s time as an explorer, before the launch of the Zambesi Expedition in 1858, Christie makes note of Livingstone’s desire to establish a British colony. Livingstone wrote Adam Sedgwick, a Professor of Geology, about his “secret” desired outcomes from the Zambesi Expedition. He wrote, “I tell to none but such as you in whom I have confidence is thus I hope it may result in an English colony in the healthy highlands of Central Africa” (366). As Christie considers this letter by Livingstone, he correctly notes this statement “cannot be legitimately seized upon as a basis for portraying him as having aggressive colonialist aspirations. As will become clear, such a depiction of Livingstone is simply not accurate” (366). Christie is correct, as one continues to read this detailed account of Livingstone’s life there are no “aggressive colonialist aspirations” in sight.

Besides the three critiques that are normally thrown at Livingstone that Christie addresses, Christie does a wonderful job at helping the reader see into Livingstone’s heart toward the Lord. For example, the reader cannot read this biography without recognizing Livingstone’s great awareness of the Lord’s providence. Time and time again, Livingstone talks about God’s providence in his life. It is seen when Livingstone writes his wife about God preserving him from an attack (203), when Livingstone writes about missions (258), when Livingstone helps to rescue some slaves (469), etc.

Because of the depth of this biography, there are many details and events Christie considers throughout. Each chapter generally consists of 6-12 months in length of time, which allows Christie to give a step-by-step look into Livingstone’s life, which makes this biography invaluable to the researcher who wants to detailed linear sketch of Livingstone’s life. However, because of the exhaustive detail, the reader needs to pay close attention to not get lost in where Livingstone is and who he is interacting with at any given time. I found myself regularly pulling out a map to chart where Livingstone was while reading through this biography so I could follow his routes through Africa.

I would recommend this book to anyone who desires to learn about the life and work of David Livingstone. It is exhaustive, but Christie divides the book into 62 chapters so the reader can consume the information in bite size pieces.

Jacob C. Boyd

First Baptist Church of Springfield, VA