A Book Review from Books At a Glance

by Ryan M. McGraw

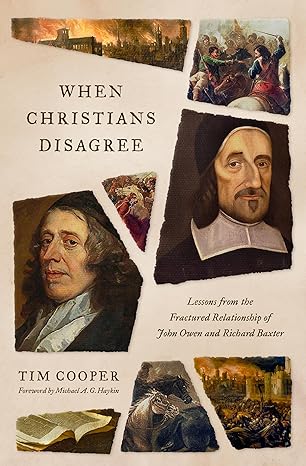

Volumes by John Owen and Richard Baxter are likely present in the libraries of most Reformed pastors, and many church members. Yet few readers likely know that Owen and Baxter disliked each other and wrote frequently against one another. In this small book, Tim Cooper condenses, popularizes, and evaluates material from his earlier gripping narrative of Owen and Baxter’s clash of personalities in John Owen, Richard Baxter, and the Formation of Non-Conformity. Drawing lessons from the strained relationship of two well-loved Puritan authors, Cooper gives some sage advice on how to navigate similar differences of background, personality, and even doctrine in ways promoting the peace of the church.

The book’s seven chapters follow the parallel historical narratives of Owen and Baxter’s lives. Though both were “good men” (chapter 1), they “brought out the worst in each other” (6). Seeking to instruct readers about the effects of life circumstances and personality on personal conflict, Cooper warns Owen and Baxter’s fans that “neither man comes out of the book looking great” (10). Chapter 2 outlines their life experiences, resulting in optimism on Owen’s part from a position of relative safety during the English Civil War, versus Baxter’s bordering despair through witnessing the devastation of the front lines. Before moving towards the first encounter between them, chapter 3 examines their opposing personalities, and chapter 4 their theological differences. Summarizing these contrasts, Cooper writes, “Owen was easily exasperated; Baxter was simply exasperating” (53). What he means is that Owen did not like being contradicted, and Baxter, despite his love for peace, often sabotaged his efforts through caustically attacking others in his books and his lack of empathy (52). Theologically, Owen’s concerns encompassed Arminianism and, increasingly, Socinianism, the latter for anti-Trinitarian views that affected a range of doctrines like Christ’s atonement and imputed righteousness. Baxter’s primary concern was lawless living or Antinomianism. Each author feared that the other compromised the gospel precisely in one of these areas. We will see below that Owen and Baxter differed most seriously over justification by faith alone and Christ’s imputed righteousness. Chapters 5-7 treat the first contact of the two men, the collision between them, and the memory that they retained from past perceived wrongs, some of which were theological and others political. In his conclusion, Cooper offers “five possibilities” for how Owen and Baxter could have gotten along better. First, they could have benefited from mediation from friends (121). Second, they could have focused on the many things that they had in common. Third, they ought to have taken Scripture texts about unity more seriously (122). Fourth, cultivating humility would have helped their relationship (123). Fifth, hindsight on the aftermath of their strained relationship gives readers a better perspective than Owen and Baxter had. These useful counsels might help readers take personal stock in their own relationships, which the study questions at the close of each chapter promote as well. The appendices presenting a timeline of Owen and Baxter’s lives in parallel, a glossary on historical terms, and a short list of recommended literature make the work more helpful too.

Despite the fact that this is compelling reading with much wise advice, a few points raise some issues that readers should be aware of. The largest one is Owen and Baxter’s substantial difference over justification and Christ’s imputed righteousness. On the surface, it may look like Owen simply “worried about the Arminians” and Socinians, and Baxter about “the Antinomians” (69), leading them to speak past each other. However, Cooper states Baxter’s position on justification clearly enough. Baxter believed in receiving a “legal righteousness” by virtue of Christ’s death, forgiving sins, and justifying sinners. Yet, he added the need for an “evangelical righteousness” through which believers eventually received Christ’s righteousness only at death through “faith, repentance, and perseverance.” Copper summarizes that “to avail themselves of this legal righteousness, believers had to bring a righteousness of their own to meet the terms of the new covenant” (62). Baxter was willing to go so far as to call such persevering obedience “merit” (63), which made him sound Socinian and Roman Catholic-leaning to Owen. Unfortunately, Cooper repeatedly says that this dispute over Christ’s righteousness “was a very narrow point of disagreement” (75). Yet justification by faith alone in Christ alone, receiving Christ’s imputed righteousness, was a primary tenet of the Protestant Reformation, which taught that believers are justified by faith without the works of the law (Rom. 3:28; Gal. 2:16). Though context and personality doubtless hindered Owen and Baxter’s ability to interact with each other, Owen (and most Reformed) would have regarded these doctrinal differences as insurmountable. Thus, Cooper’s “five possibilities” for promoting unity between these men could only go so far. While this point should not detract from this page-turning narrative, or from Cooper’s practical lessons, modern Reformed readers are often shocked when they discover what Baxter believed about justification, instilling a measure of distrust in his writings. Despite Owen’s personal flaws, we end up sympathizing with him against Baxter here.

This reviewer is thankful that authors like Cooper are writing books like these, introducing the fruits of superb historical scholarship to a popular audience. Though likely disappointing some by taking the luster off of a couple of heroes, this work will be hard to put down, instructive, and enlightening to many readers. Without minimizing doctrinal differences between Owen and Baxter, we should undeniably take warning from the broader issues that threatened to overshadow more important ones.

Ryan McGraw

Greenville Presbyterian Theological Seminary