A Book Review from Books At a Glance

by William Varner

When I was asked by the editor of this notable volume to offer a review, I gladly accepted his invitation and looked forward to receiving the finished work. Since I was trained in a Presbyterian related institution (Faith Theological Seminary) and was familiar with American Reformed theology, I was very aware of R. L. Dabney’s Systematic Theology (1887), republished by Banner of Truth Trust in 2002. I also had often heard that Dabney served as a chaplain to Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson in the American Civil War. Therefore, both because of his theology and also because of his role in the war, I anticipated with enthusiasm this volume. The following will also explain my particular personal enthusiasm.

I grew up in the South without any real devotion to my Civil War heritage, even though my state of South Carolina was the first to secede from the Union. When I relocated to the North, never to permanently return to the South, I was surprised at how many people queried me about the Civil War, and I honestly did not have much of a response. So I developed a hobby of reading about the Civil War, or “The War Between the States,” as it is often called in the South. I amassed a rather significant library about the War in general and the Southern role in particular. In the decade of the 1980’s, I even became a Civil War re-enactor, brigading in both a blue and a gray uniform at such important battlefields as Antietam, Gettysburg, and Fredericksburg. People thought that I would re-enact as a chaplain, but I refused to do so because I wanted to get a feel of what life was like “in the trenches” – so to speak – for “Johnny Reb” and “Billy Yank.”

This collection of sermons by R. L. Dabney has long been hidden in the dusty shelves of university libraries. We owe a thanks to the editor for selecting some of the best homiletical examples from Dabney’s ministry to the troops and re-issuing them, some for the very first time! One of the most valuable aspects of this book is the excellent “Introduction” (20-37) in which the editor summarizes Dabney’s role and ministry not only during the war but before and after it as well. He is careful to mention Jackson’s deep appreciation of Dabney as his staff chaplain. The collection is an essential read that places twenty sermons of Dabney and four special appendices within the historical context of his significant life and ministry. Peters has included all the main events in the life of the subject, but omits mention of one aspect of his life and writing to which we will return after celebrating the special feature of this volume, the sermons that comprise the substance of the book.

Peters includes not only the text of each sermon, but also the date it was originally preached, the location where it was preached, and any special circumstances surrounding it. The first five sermons were delivered before the beginning of the war in the spring of 1861. The following fifteen sermons were originally delivered during the war, the last one dated in February 1865 in the pulpit of a Presbyterian Church in Petersburg, Virginia. Students of the conflict will remember that Petersburg, along with its neighbor Richmond, were the last stands of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia as these two cities were besieged for many months by U.S. Grant’s Union forces. Realizing this adds a bit of intense drama to the context in which these sermons were delivered. These messages were possibly the last sermons that many of these “boys” would ever hear!

What was a sermon of R. L. Dabney like? First of all, contrary to what one might assume, the messages were not extremely long. Though they were shorter than typical church sermons, Dabney did not waste words. A later comment in the book estimates that each sermon was usually not longer than thirty minutes in length. That is quite short compared to other sermons delivered in churches by nineteenth century Protestant clergymen.

Secondly, the type of the sermons, probably consistent with what Dabney would deliver elsewhere, would be that they were “textual” in nature. I mean by that term that they were based on a text of only one verse, two at the most. We could compare that type of sermon with what could be called “expository” sermons, those being an exposition of a paragraph or longer text. If the reader is familiar with the sermons of Dabney’s contemporary across the Atlantic, Charles Haddon Spurgeon, then one will recognize that the thousands of Spurgeon’s sermons were almost always “textual” in nature. For example, only one of Dabney’s sermons is from a text longer than two verses. It is sermon 19, titled “Faith,” and the text is Romans 10:6-10. Interestingly, and to illustrate my above point, the sub-title of this excellent homily is “An Expository Sermon”!

Thirdly, Dabney’s method of expounding a text was to ask a question about its meaning and then offer a series of answers to that question. Let us illustrate what that means from the very first sermon in the collection. This message was titled “Getting without Paying: A Sermon on Exodus 20:15: ‘Thou shalt not steal.’” To summarize his points, Dabney elaborated the meaning of theft as using false weights and measures; laboring unfaithfully for an employer; being fraudulent in bargains; availing oneself of legal advantages; taking liberties with the public purse; heedless contracting of debts; and gambling. The last manifestation of stealing as gambling must have been one that Dabney had often witnessed among the soldiers because he elaborates on it extensively (53-56). His later sermon on “Profaning God’s Name” from Exodus 20:9 is handled in a similar fashion. We profane His name by needless oath-taking; by irreverent uses of God’s Word; by heartless and formal worship; by irreverence in the sacraments; by exclamations and imprecations; by perjury; by false swearing; and by profane conversation (67-74). One can only imagine that this type of preaching is similar to Dabney’s teaching of systematic theology, namely by elaborating on theological propositions about God and His truths.

Furthermore, the editor has done the twenty-first century reader a service by providing a glossary of words and expressions that might need clarification (304-17). The reader might be able to discern the meaning of these terms from the context, but all should be thankful for his explaining further such terms as “accordant” as agreeing; “actuated” as motivated; “anodyne” as drug; and “aspirant” as seeker – to mention only a few.

The sermons are timely, in light of the war; applicational and not heady nor overly theoretical; and are warmly devotional and related to life. While not being morbid, they were certainly very appropriate to soldiers facing the realities of life and of death. The style of the sermons may take some getting used to, but Robert Dabney’s heart as a pastor and not just as a military officer comes through clearly in each of them.

In some ways, I am hesitant to offer any concluding critique because of my obvious delight in this collection of sermons. My critique is not so much in what is included in Dabney’s words as in what is omitted! In his listing of Dabney’s books written after the war (36), Peters omits one of his most widely read volumes. I refer to the following: A Defence of Virginia and Through Her, of the South in Recent and Pending Contests Against the Sectional Party; 1867; repr. Harrisonburg, VA: Sprinkle Publications, 1991. Peters does include it in his bibliography (341). This book was originally published in 1867 and was by far his most widely read work at the time. In this work, Dabney not only defends the Southern departure from the Union, but also defends the Southern practice of slavery.

I will only mention a few items of significance from this volume. In 1867, the Synod of Virginia was considering whether or not black men should be ordained to the full work of the gospel ministry. Dabney gave an impassioned address to the Synod on the “Ecclesiastical Equality of Negroes,” pleading with his fellow presbyters not to approve it. In the address, he claims that a providential, “insuperable difference of race, made by God and not by man, and of character and social condition, makes it plainly impossible for a black man to teach and rule white Christians to edification” (201). For Dabney, the issue was quite crucial, and he expressed himself fervently about it: “Every hope of the existence of church and of state, and of civilization itself, hangs upon our arduous effort to defeat the doctrine of negro suffrage” (205). He added: “when the party of the white man’s supremacy is gathering in such resistless might . . . why attach our Presbyterianism to a doomed cause?” (208)

It is quite significant and unfortunate that the theologian Dabney takes a theological approach to this issue and appeals to Providence as one of the justifications for slavery. In other words, he argued that slavery was where those who were black found themselves, so in slavery they should have accepted His providential dealings. Apart from that theological argument, however, the above quotes also point out the personal prejudice that Dabney had against black Americans, revealing that he considered them as inferior human beings.

Despite his categorically unbiblical perspective on the dignity of human beings, I still deeply appreciate Dabney’s sermons and his theological writings. I also can still appreciate Martin Luther despite his virulent antisemitism, as I also can still appreciate John Calvin despite his unwillingness to oppose the burning of Servetus. My concluding suggestion is that readers still should benefit from this wonderful collection of sermons. Abraham and David had evident faults and God did not cancel them from His program of redemption!

William Varner

The Master’s University

Note: This review was first published in TMSJ 33, no. 2, pp. 339-42. Republished here with permission.

Buy the books

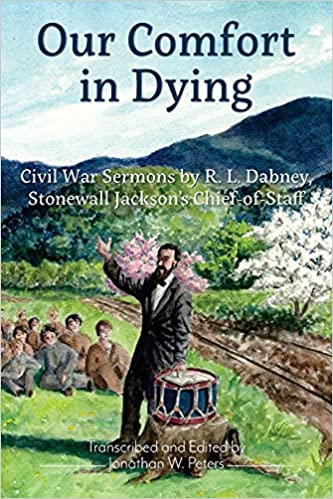

OUR COMFORT IN DYING: CIVIL WAR SERMONS BY R. L. DABNEY, STONEWALL JACKSON'S CHIEF OF STAFF, transcribed and edited by Jonathan W. Peters