About the Editor

Chad O. Brand has served as a pastor and has taught theology and church history for more than twenty years at three Baptist colleges and seminaries.

Introduction

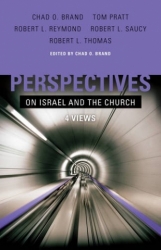

This book presents four perspectives on the relationship between Israel and the church. Robert Reymond represents traditional covenant theology, Robert Thomas classical dispensationalism, Robert Saucy progressive dispensationalism, and Chad Brand and Tom Pratt Jr. progressive covenantalism. Each position is articulated in an essay, which is then critiqued in response by the other contributors. The book deals with eschatology, hermeneutics, issues of continuity and discontinuity, the nature of the people of God, covenants, salvation history, and other topics that affect how we interpret Israel and the church. The writers engage in both biblical and systematic theology when they articulate their own views and critique the views of their fellow contributors.

Table of Contents

Introduction: Chad Brand

Chapter 1 The Traditional Covenantal View: Robert Reymond

Responses

Chapter 2 The Traditional Dispensational View: Robert Thomas

Responses

Chapter 3 The Progressive Dispensational View: Robert Saucy

Responses

Chapter 4 The Progressive Covenant View: Chad Brand and Tom Pratt Jr.

Responses

Summary

The responses at the end of each essay are not covered in the following summary. There are two reasons for this, the first being that the responses are fairly brief. The second—and more important—reason is that the main points in the responses are also usually covered in the essays.

Chapter 1

The Traditional Covenantal View

The three key components of historic covenant theology are: 1. The unity and continuity of redemptive history, 2. The unity of the covenant of grace and the people of God, and, 3. OT saints were saved by faith in the Messiah and his anticipated sacrificial work. The Reformers saw how God’s glory and redemptive purposes in the world are administrated through covenants. Adam sinned and violated the covenant of works, but in mercy God made a covenant of grace (which was a covenant of works with Christ) so that sinners could be saved. There is only one covenant of grace, of which the other biblical covenants are administrations.

Dispensational theology differs as to the number of dispensations, but they all agree that there is the Mosaic era, the present dispensation of grace, and the future millennial age. They also agree that OT saints were not saved by conscious trust in the sacrifice and suffering of the Messiah, since God had not yet revealed that the Messiah had to die. Yet the exodus from Egypt showed the necessity of sacrificial blood, and the NT authors point to numerous OT prophecies that talk about the suffering and death of Christ. The elect church of God constitutes one people through the ages, and all of them are saved by faith in Christ, either in his anticipated or accomplished work. The new covenant is an outworking of the covenant with Abraham.

Dispensationalists appeal to texts that speak of the mystery of the kingdom to support their view that God had not revealed the suffering of the Messiah, but these texts are talking about the growth of the kingdom before its consummation in power and glory. The OT clearly reveals the suffering of the Messiah, so this cannot be the mystery in view. In Ephesians the mystery is not that the Messiah will suffer, but rather that the Gentiles are included with the Jews as the one people of God. The solution to dispensationalism’s difficulties is found in covenant theology, with its view of the unity of the people of God and one covenant of grace that centers on the suffering Messiah.

Covenant theology recognizes that the land promises to Israel in the OT are typological, and that the ethnic nation of Israel is not promised physical geography forever and ever—rather, the land promise is for the people of God and comes to fulfillment in a much greater way. When the covenant of grace comes to its expression in the Abrahamic covenant, all other covenantal administrations attach back to the Abrahamic and work out the fulfillment of God’s promises to Abraham. God is the God of Abraham and Abraham’s spiritual offspring forever, and it is this reality that extends into the future state and the renewed cosmos. The new covenant—with Christ as the mediator—is an administration that extends and unfolds the Abrahamic covenant.

Land does not become important with Abraham: it was an essential part of God’s creation purpose in Eden. The restoration of a place for God’s people was a redemptive promise that finds fulfillment in the new heavens and new earth, not in Palestine. The NT clearly states that Abraham did not consider any land on this earth to be his home, but looked for a heavenly city. Israel receives land, but the entire Mosaic covenant was provisional and temporary. Jesus taught…

[To continue reading this summary, please see below....]The remainder of this article is premium content. Become a member to continue reading.

Already have an account? Sign In