John Owen and his Times: Introduction to the John Owen Project

Interview with Michael Haykin

Greetings! I’m Fred Zaspel and welcome to another Author Interview here at Books At a Glance.

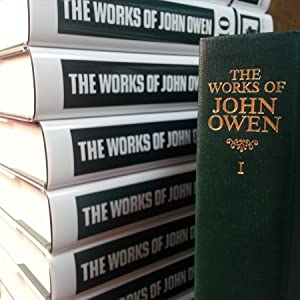

Did you ever wish you could read through all sixteen volumes of John Owen? That will be our task this year at Books At a Glance, only we’ll do it in small, summarized pieces.

Before we begin we wanted to provide some historical background, and to help us with that is our favorite church historian, Dr. Michael Haykin, of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary.

Michael, great to have you with us again.

Haykin:

Great to be with you.

Zaspel:

Before we talk about the puritans, give us the background. Maybe start with the Reformation, Henry VIII, Elizabeth, and so on. Politically and religiously, what was going on?

Haykin:

Owen’s world is in major turmoil. It had been since the 15’ teens. He is born in 1616, the year that William Shakespeare dies. Ever since the 15’ teens almost exactly 100 years earlier, the reformation began in Europe. What began in Luther’s mind as a small discussion of the viability of the thing called indulgences, that we can purchase our salvation through a grant given by the papacy, became the beginning of The Reformation. It plunged Europe into religious turmoil and because of the Constantinian union of church and state that had been in Europe since the 300’s it was also political turmoil. By the time Owen was born, there were already religious wars in Europe. These were the so-called period of the French civil wars beginning in the 1560s and heightened with the massacre on August 24, 1572. There was a long series of civil wars that weren’t concluded until 1598. Within a few years of Owen being born was the 30-year war beginning in 1618-1648. This was a religious war of Protestant Spain fighting against Protestant Germany, particularly bolstered by Sweden.

It is a world in deep turmoil over religion. It would be foundational to The Enlightenment which is a reaction to two centuries of political religious turmoil of going secular. In England, The Reformation had come in 1520 with reformers particularly located in Cambridge which was kind of Ground Zero. William Tyndale came out of this world. We do not know how he was converted but he was by 1522. He begins to translate the Bible into English. This becomes foundational to the English reformation.

There was a complexity to this reformation because Henry VIII was eager to dissolve a marriage that he was involved in. For him, it was a question of not religion, but the fact she could not produce a male heir. He became convinced their marriage was not real in the eyes of God. Henry’s father arranged the marriage with Spain to have an ally. When Arthur died within a year, he was able to get a dispensation from the pope to the effect that the marriage had never been formally consummated. Therefore, they could marry Henry off to Catherine. Henry was deeply frustrated because he couldn’t have a male heir. He read in Leviticus and came across the statement that you should not have your brother’s wife. This has to do with divorce and remarriage. Henry takes this as a principle. He knew his Bible and wrote a book against Luther. Henry would have gotten the annulment he wanted because he was willing to pay, and Rome was willing to say Catherine was never his legal wife. All of this did not please Henry. He eventually divorces his wife and makes himself the head of the Church of England. This creates a crisis in the kingdom, and they must swear allegiance to him.

Then there are the German, Swiss, and French reformations. You have this very strong co-mingling of church and religion. When I was taught the reformation, I was taught it by a scholar who was a disciple of A.G. Dickens. He emphasized two different wings of the reformation. You must recognize the real reformation begins with Tyndale and the Bible and these men being converted. It is also mixed up with Henry. Henry’s theological convictions are influx. It is not until Edward the 6th that The Reformation begins to move with alacrity in England. Calvin writes to the young Edward when he becomes king in 1547 and describes him as a young Josiah being a leader in The Reformation. He dies in 1553 and he is succeeded by his half-sister Mary.

Mary had a deep unbounded hatred for Protestantism in any shape or form. She blamed her father for being divorced because of it. This was not at all true. There were key Protestants like Cranmer who were caught up in those kinds of proceedings so she cannot forgive Cranmer or Protestants in general. There was a period of repression and close to three hundred Protestants were executed which is unheard of in England. The Spanish inquisition rids England of Protestantism. There were Calvinist centers where they had learned that unless something is commanded in the word of God it should have no part in the worship and governance of the church. These men are thrilled to bits that they have a queen. The church still has a way to go in terms of reform. The use of the Apocrypha for example needed to be stopped. Most were exiles under Mary. She was the head of the church. Most had embraced a Presbyterian form of church government.

Owen said very little about his family background. You could sum it up in less than a page of what Owen tells us explicitly about his personal life. His father was a painful laborer in the vineyard of the Lord all the days of his life. He meant that he was a very careful worker. This is code for the fact that his father was a Puritan. Owen was raised by a man who would have gone through all the tension under Elizabeth. He continued his ministry very conscious that at any time he could be called to account by his local bishop and his ministry ended. This is the world in which Owen was born.

Then Congregationalism emerged in England in the 1580s. Before that, you could find it in France. In the French Calvinist churches in France, the governance was Presbyterian. But in the early 1560s, there is a French Calvinist thinker named Jean Morély. He enunciated what becomes Congregationalism. It plunged the church in Paris into controversy. Calvin did not say anything but his coworker in Geneva defended Presbyterianism. The controversy comes to an end at the St. Bartholomew massacre. Most of the leading figures who supported Morély were martyred.

Owen ended up in Norfolk, England. Norridge, the leading town of Norfolk, was a major center of Puritanism. Several of the Pilgrim’s fathers and mothers came from Norfolk. Morély got there in the 1570s and lived another 20 years. It was in the early 1580s that Norfolk Puritans enunciated a theological perspective that is identical to Morély. This is the same text and argument for the separation of church and state.

Robert Brown was a rector and writes a book, Reformation without Tarrying for Any. In other words, we do not need to wait for the magistrate. Presbyterianism was yoked to a Constantinian view of church and state. Elizabeth was upset by this, and it was anarchy to her. In the classical division of politics, you had a monarchy which a lot of writers equated with Episcopacy. You had aristocracy which a lot of writers equated with Presbyterianism. You had democracy which was equated with Congregationalism. That kind of thinking was still there during the reformation. Elizabeth brutally tries to put down early Congregationalism. Brown recants his views and is allowed to serve in the church of England again.

After this several leaders were martyred in London. Congregationalism to some degree went underground. Eventually several of them left for Holland. It was in that context that John Smith embraced Baptist polity in terms of Baptism. He was a Congregationalist first but only believed adults could be baptized and join a congregation. All of this was significant for John Owen. In the 1630s at Owen’s first church, he became a Congregationalist. There are some people that say he was thinking about going back to Presbyterianism. He was appreciative of much in Presbyterianism. He was not going to go back to that form of church government.

Zaspel:

Now talk to us about John Owen. Who was he, and give us a sketch of his career.

Haykin:

He was born in 1616, the year Shakespeare died. That gives us perspective. He died in 1683. He probably saw the most tumultuous century of British history. The 17th century is a world turned upside down. It was a world in which Owen knew while he was growing up. It had to do with parish life, the stability of the monarchy, and aristocracy. England was plunged into a religious civil war. He had two or three brothers, one of them named Philemon, who perished in Ireland fighting the troops of Oliver Cromwell. Another brother became a minister like him. He was born in a little town not far from Oxford.

Because of his father’s status, he was able to go to Oxford as a student. He took to Oxford like a duck to water. The problem is that he went to Oxford in the 1630s at a very difficult time. At this point, the monarch was Charles I. In the late 1620s, when parliament did not grant him money to engage in a war with France, he dissolved parliament. He decided he would rule England by himself. He said he was appointed by God. He knew he would face God in judgment, but he decided what he wanted. He is determined to unify the church.

Charles I appointed as his Archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud. He not only hated the Puritans but was also convinced the reformation had gone too far. He wanted to bring back various elements of the pre-reformed church in England. By this point in time, new viewpoints were being injected. There was a very strong Arminian strain. There were spies in churches that would report improper things. These pastors were arrested and abused for not following Laud’s rules. This came into the university.

Owen obtained an MA and a BA in the 1630s. This must be seen against the background that about four percent went to university at this time. Owen felt the university of Oxford would be his abode for the rest of his life but with William Laud, he would never get a teaching position there. He became a chaplain. This would have continued if it were not for the war. The king was drawn into a war with his own parliament. This led to a showdown in 1642 and Charles came into parliament with soldiers. Charles was a devoted husband and father but not smart when it came to politics.

Owen went up to London in 1642 and had an experience there with his cousin. Arthur Jackson was preaching, and Owen would never forget that sermon on assurance of salvation. He was intellectually a Christian but heard this sermon and was convinced of Calvinism and assurance of salvation. Without a deep work of God in the heart, there is no assurance. In the 1640s this learning was quickened because of the Quakers. They claimed sanction by the Spirit. Owen amounts to the largest collection on pneumatology in the English language. This is the study of the work of the Spirit.

He then became a Congregationalist. This was where he wrote, The Death of Death in the Death of Christ. He became close friends with Oliver Cromwell. The king was executed, and Owen was there. Owen had to preach before parliament the day after the execution and preached from 2 Kings on the wickedness of Manasseh. He talked about cleansing from such wicked men. This is England’s first involvement with the republican government. The American Revolution does not come out of the blue. It emerges from Congregationalism.

Owen and Cromwell were very close. He was his chaplain. In the 1650’s Owen was appointed vice-chancellor of Oxford and he cleaned up Oxford. One of the great political architects, John Locke, sat under John Owen. He would have heard Owen preach his series of sermons on the mortification of sin. This was given to 16-year-old students at Oxford.

In the 1650’s everything changed. Cromwell dies and the king’s son returned. One of Owen’s friends, George Monk, felt England was slipping into anarchy. He thought it was better to have a monarch rather than anarchy. Charles II was a duplicitous individual. He probably had more royal mistresses you could count and numerous illegitimate children. His court was a body house. The king was a crypto catholic and probably would have given toleration to the Puritan’s which he pledged he would. But the men who came to power with him were determined to destroy the Puritans. They were destroyed as a military and educational force, and any influence it had in the church. To be honest he succeeded. He passed laws that prevented Puritans from graduating, holding office in the Navy, and holding political office of any shape or form.

These laws were not always obeyed in the letter of the law and often they were broken. Those who refused to go along with the book of the common prayer were expelled on August 24th, this entailed 2,000 ministers. Their lives were now precarious until 1688 when the Act of Toleration was passed which underlies the freedom of religion. The first major freedom that was given was freedom of religion. This passes into the whole legal framework of English law. Between the restoration of the monarchy in 1660 and 1688 it was brutal.

Owen himself because he had some very close friends in the court was never really arrested for more than a day. His house was raided. They found the equivalent of half a dozen shotguns and twelve pikes. By the 1670s Owen was fed up with the monarchy again. He was involved tangentially with plotters against the king. He was never arrested for plotting. When he died in 1683, he died with the assurance of salvation but died in grievous days. There are probably three or four great Puritan leaders and Owen is one of them. Baxter was the key theologian of the Presbyterian’s and Owen was the key to Congregationalist’s and their inability to come together hurt Puritans big time.

Zaspel:

You and Matthew Barrett wrote a book a few years ago on John Owen. It’s entitled, Owen on the Christian Life: Living for the Glory of God in Christ. Tell us about it before I let you go here.

Haykin:

It was a great opportunity. Initially, I did not want to do it. I wanted to do something on Andrew Fuller. Matthew Barrett wrote on the trinity, atonement, and heaven. We looked at key themes surrounding Owen. It is a great introduction to Owen. I do not know of anything else out there like this. Owen is such a central figure in Puritanism. I think Owen was the right choice to do this on.

Zaspel:

Steve West, one of our editors at Books At a Glance, has taken on the herculean task of summarizing all sixteen volumes of John Owen. We will be posting these in fifty installments—one each week throughout this coming year, 2022. Each summary will be just four to ten pages in length, so this way you can get all of Owen in bitesize pieces.

If you’re like most of us and can’t find the time to read through all of Owen yourself, here’s your chance to take it in the easy way. Click the link below to join us.

Michael, thanks so much for providing this historical background for us. Always great to have you with us.

Haykin:

Thank you!

Buy the books

THE WORKS OF JOHN OWEN, by John Owen