An Author Interview from Books At a Glance

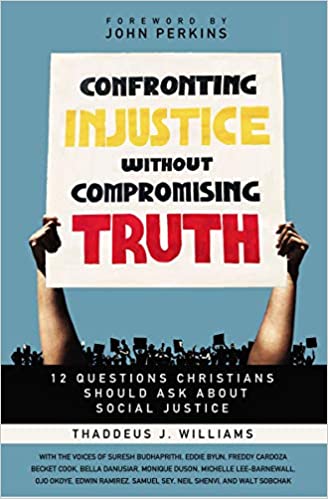

You can hardly imagine a more contemporary topic than social justice, and even if you’re sick of hearing about it I suspect you’ll be interested in this new book, Confronting Injustice without Compromising Truth: 12 Questions Christians Should Ask About Social Justice.

I’m Fred Zaspel, and welcome to another Author Interview from Books At a Glance. Today we are talking to Dr. Thaddeus Williams about this important new book. Thaddeus, welcome, and congratulations on your new book!

Williams:

Thank you! It is a joy to be with you.

Zaspel:

Tell us what your book is all about and what it is you hope to contribute.

Williams:

We have seen in the last five years a deep upset of Christians trying to sort out the hot button issues of the day. Controversial, combustible questions. In 2021, how do we think about biblical justice? Wrapped up in that word combination would be words like racism, abortion, gender sexuality, and the definition of marriage, socialism, and capitalism. This book is an attempt to give believers around the globe an approach that starts by taking God’s word seriously. More seriously than we take the trends and polarized categories of the culture. How do we think biblically about social justice? The subtitle is: “12 Questions Christians Should Ask About Social Justice.” This helps us divide the wheat from the chaff.

Zaspel:

You mention near the very beginning that one of the great changes in our culture that you have witnessed is the shift from a “Don’t judge!” consensus to that of perhaps the most judgmental society in history. Flesh that out for us a bit.

Williams:

I am very much a child of the nineties. The spirit of the age was there is no such thing as sin except calling anything sin. The anything goes heyday of post modernism. I started teaching 20 years ago. I had this deep hunch that anything goes relativism has a shelf life. It can only last for so long. You see this all through history. Whether it is the ancient Greeks or Romans. In Europe, the late 19th or 20th century. Whenever relativistic ideologies take root, they tend to generate a pendulum swing in the opposite direction. We just are not wired by our creator for anything goes relativism. We are designed to live and breathe and die for something bigger than ourselves. I have been anticipating for the last 15 years at least that this pendulum would swing hard from anything goes to some form of dogmatism. An absolute system that claims to be king of the hill. That is what we are living through, this cultural shift to anything goes to almost nothing goes unless you abide by our ever-evolving standard of justice. The issue behind the issue, with cancel culture and social media mobs. You have a generation that has been raised to do whatever they feel like. It’s so unsatisfying that they pass on a grand moral crusade. It satisfies a very deep God built-in need. Even if it is misdirected.

Zaspel:

It is kind of a new fundamentalism on the left, is it not?

Williams:

Yes. What we are dealing with here is not a rival political series. At base level, it is seeking to answer existential human needs. The same needs that the Gospel answers. How do I get justified? How do I achieve my not guilty sentence? That is universal. A Hindu plunges into the Ganges river. If you are a Jew at the Wailing Wall. If you are a Muslim on your knees towards Mecca five times a day. Or a Catholic in the confessional booth. We are all after the same thing. The same justification. We all want to feel like we are on the right side of history. That is the deep existential need that today’s social justice movements go by.

Zaspel:

What is “social justice”? And sort out for us any mistaken contemporary notions from a more biblically informed notion.

Williams:

The term social justice, a lot of people hear and automatically assume we are talking about Marxism or some form of far leftism. The truth is historically it was Christian theologians who crafted the church about 250-300 years ago the term was co-opted. And the mainstream today, that combination often does jive with deeply Marxist perspective. We see this example in the Black Lives Matter organization. The distinction of the phrase “black lives matter” as a truth claim, as Christians we can deeply affirm this saying. Black lives bear the image of God. But BLM the organization, their founders are trained Marxist. They are using social justice to express their trained Marxist ideologies. That is one way of defining the term which in the book I refer to as social justice B. The division of social justice that as Christians, we should be very wary of, resistant to. It is deeply damaging to God’s image-bearers.

On the other hand, you have what I describe as social justice A. It is the kind of Christians we should be deeply committed to and passionate about. For example, in church history, our brothers and sisters in the 1st and 2nd centuries were passionate about social justice. In the infanticide of the Roman Empire, tiny image-bearers were discarded like trash. Because of their faith, not in spite of their faith, they went to those literal human dumps and rescued societies unwanted and brought them into their homes as cherished sons and daughters. Social justice A is William Wilberforce, who in the UK, helped overthrow the institution of slavery. Social justice A is what Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, and Frederick Douglas were doing in the US because of their faith to overthrow and abolish slavery. Dietrich Bonhoeffer exposed the evil of Hitler. That is important in the conversation, to say it is not about those who care about social justice and those who do not. But it is about those who want to continue the legacy of biblically inspired justice. We must follow on the foot heels of Bonhoeffer and Wilberforce in the early church. In contrast, those who are adopting today’s ideologies are coming from a very different worldview.

Zaspel:

Explain for us how you relate the question of injustice, in turn, to God, humanity as the image of God, and idolatry. How are these concepts important for understanding this issue?

Williams:

The starting point that biblical justice begins with is the godhood of God. That is a mark if you look at Martin Luther King Jr. in his letter from Birmingham jail. 90% of that letter is saying there is law above the law. There are unjust human laws that are saying essentially if you have less melanin in your skin cells you deserve a better buff seat and are more human. MLK is saying, “No! That law is an unjust law because it does not jive with the transcended law of our creator.” One of the things that made MLK’s vision of justice compelling is that it had a transcendent frame. It was bigger and above us to look to. You see that throughout all the examples I just gave. Wilberforce, if he was just looking to humans as supreme, we would have to say, “Well human value is a human construct. Most of the British culture is that slavery is okay. Who am I to go against the highest standard?” The inspiring method that Wilberforce had was a law above the law because he was a Christian theist. I argue in the book that all true justice starts vertically with who is God? What does God do as God? A lot of what I am calling social justice B God is either irrelevant or antagonistic to their cause.

Your second dimension of the question is what about human nature? This could easily be a three-hour lecture. The condensed version is that biblically every human being from every demographic regardless of skin tone, social status, or our sex, we are united in Adam in our fallenness. That means I cannot appeal to my skin tone or anything and say that makes me superior. As Paul makes clear in Romans 3, “All have sinned and fall short of the glory of God.” That basic insight of how universal human simpleness is. That swings like a wrecking ball through any kind of identity politics whether it’s coming from the far right, “I am white, so I am better”, or the far left, “I am not white, I am on the right side of history.” Scripture cuts through all that with the pride deflating reality that all have sinned and fall short of God’s glory. Beyond our “in Adam” identity, is our “in the second Adam,” in Christ’s identity. This gives me a way of looking at brothers and sisters across all demographics.

We might be on different levels of the socio-economic scale, different melanin in our skin cell, XX or XY sex. They are my brother or sister because we are adopted by the same Father, redeemed by the same Son, inhabited by the same Spirit, so we are family. That is the biblical answer to how to approach our humanness. Very different from what I call social justice B. It divides everyone into these categories. Oppressed or oppressor. All based not on the actual person but on group identity. It is just a recipe for endless division and strife. Idolatry can happen on both sides of the political spectrum. I talk about in the book how the further we drift, the extremes of the right, it’s easy to make a false god out of the self. The idolatry can be thinking as an isolated individual, “My actions do not affect other people.” It’s easy to make the Lordship of Jesus not making a difference in the here and now. When you look at some idols on the left. The god of self, which means, how I feel, self-defined identity, are the unquestionable standard. Anyone who questions how I define myself is automatically an oppressor. The false god of state, which is, I look to the government as my messiah. They will usher in the new heavens and earth through passing my policies. The false god of social acceptance. In the Christian context, we like to be liked. We want the world pat on the back.

Zaspel:

Let me ask you your own question from page 41: “How do we meet our irrepressible God-given need to belong in groups without those groups becoming self-righteous and resorting to full-blown tribal warfare?”

Williams:

Let me answer with two quick stories. At the end of each chapter is a story of someone who has experienced the liberating power of the Gospel from far left or right. One of the stories comes from my friend Edwin Ramirez. He was a solid Bible-believing Christian and then he slowly started drifting to unbiblical social justice ideology. It got to the point where he was bitter and resentful. He would go to church as a minority and look around the room and think these people are his oppressors. They do not get it and do not know what it is like to have brown skin in this culture. Over a couple of years the fruit of the Spirit: love, joy, peace, and patience were gradually replaced with resentment, bitterness, and assuming the worst. He tells the story about one day in the rural church that was predominantly white, they were singing a hymn and he was standing there with his arms crossed, looking around the room, judging everyone for not being as woke as he was. Until his eyes fell on this elderly white woman in the front row who had her arms outstretched, belting out in worship. Somehow at that moment, it struck him that she was his sister in Christ. Deeper than anything she is his sister, adopted by the same Father, redeemed by the Son, inhabited by the same Spirit. We all have a need to connect. Are we going to connect on society’s defined boundaries, or on Scripture defined unity which transcends those boundaries, to draw people into family?

I shared another story in the book. A former student of mine. He took my Foundation to Christian Thought class at Biola University about 7 years ago. At the time he was deeply racist. He was a white supremacist, a neo-Nazi. I did not know it for sure at the time. I sort of had a hunch. He took my classes over four years. I watched this radical transformation where he was hateful and arrogant. By the time he graduated he looked different. His countenance and physical expression of his soul’s interior state was different. He was passionate about the Gospel and evangelism. I asked him when I was writing the book, “By any chance were you a Nazi in college and did Jesus set you free from that?” I got an email back the same day and he said, “Yes that’s exactly my story, Jesus set me free from neo-Nazism and racism.” I asked, “What was it that helped you in being set free?” He said, “It was hearing the Gospel. If all have sinned and fallen short of the glory of God, I cannot look at my white skin and think I am better than anyone. If Jesus seeks to save people from every tongue, tribe, and nation, that is a wrecking ball of neo-Nazism.” He is now training for lifelong ministry. He is in community with brothers and sisters with different skin tones than him precisely because of the Gospel. The fundamental need to belong is answered through a church that is united in Christ. Any other system is going to find some way to create the hierarchy of being better than others. Entry into church is not performance or skin tone but it is 100% that we are saved by the free grace of God. It is a community where it is impossible to be prideful.

Zaspel:

Your book is essentially structured around twelve questions. I have already pre-empted this a bit, but highlight for us those twelve questions, perhaps with just a brief explanation of each.

Williams:

Those twelve questions are grouped into four categories. Three questions about social justice and worship, three about social justice and community, three about salvation, three about knowledge or the pursuit of truth. The questions about worship are about God. Does your view of social justice take the godhood of God seriously? If it does not it is not real biblical justice. Does it take the image of God seriously? Does our vision have us on our knees to any counterfeit idol of social justice?

The second set of questions. Social justice and community, we think about whether our vision of social justice takes any group identity more seriously than our shared identity in Adam. Our shared fallenness. Do we look at it from a Romans 3 argument or our identity in Christ? If it highlights any other identity category more than those two it’s not biblical justice. Does it resort to the bites of propaganda? Another question is simply the fruit question. What fruit is our vision of social justice bearing in our own hearts? Is it creating the fruit of the Spirit, marked by love, joy, etc? False social justice is marked by the anti-fruit of the Spirit. Rage, self-righteousness, and assuming the worst in other people.

In the next set of six questions, there are three about social justice and salvation. The first is the disparity question. In social justice B, the way you spot oppression is to look for any disparate outcome. If there is an unequal outcome then the assumption is this, it is automatically an injustice or discrimination. On the other hand, social justice A, the biblical kind, wants to acknowledge what Psalm 94 says. We want to be aware of those who frame injustice by statute. Pharaoh enslaving the Jews is not just his individual sin. Nebuchadnezzar, decreeing idolatry, forcing them to bow to the golden image. Social justice B identifies an evil system base on any disparate outcome. That leads us down a road to ultimately some kind of totalitarianism. I ask what I call the color question. Does our vision of social justice stir up racial strife? Here I get into some of the most controversial landmines, written conversations on things like police brutality, and economic disparities between black and white communities. I walk through some of the hard facts on those questions because the truth is most people’s perception is so far removed of what is happening there. If we are not asking the hard questions, then we are dealing with the real issues behind the issues. They often get labeled as racists, bigots, or haters. The Gospel question, it is massively important. If we do not keep the first thing, the first thing we are in trouble. The good news, that a holy God redeems fallen sinners, through the substitutionary death and bodily resurrection of Jesus, through no credit of our own, but by grace alone, then we are not doing justice. We lose the Gospel, and our justice will be twisted into something other than justice.

The final three questions are about social justice and knowledge. The first question is what I call the tunnel vision question. We can bind to a certain ideology, where everything is about Christians forcing down morality down throats. When we bind to epistemology that interprets all of reality through a specific category, we have tunnel vision, and it blinds us to reality. Next is the suffering question. To what extent will we go if we are filling people’s heads up with tribe thinking? We are convincing them they are oppressed in all directions. To what extent are we adding to the suffering they are already going through? Lastly, the standpoint question. Have we turned the quest for truth into an identity game? We weigh the credibility of ideas not based on faithfulness to Scripture, or facts and evidence. It is purely based on the melanin of the person articulating the idea.

Zaspel:

Throughout you have talked about “Justice A” and “Justice B.” Give us a summary.

Williams:

Social justice A, love is not easily offended, is straight from Scripture. We are to have no gods before God. Regardless of your ethnicity you are fallen and guilty in Adam and only redeemed by a new identity in Christ. It confronts us with the reality that our works are filthy rags. Christ is the only ground for a righteous standing. There is no condemnation for those in Christ Jesus. There is something beautiful about the differences between male and female. They are called very good in Genesis 2. We cannot erase those without losing something precious. In biblical justice, everyone bears God’s image. We care about tiny image-bearers in the womb and their mothers who are often exploited by a greedy abortion industry.

Social justice B encourages us to be offended and chronically triggered. You bow down to either yourself as the final standard on reality or bow down to the state or social acceptance. Your guilt is credited based on skin tone; you must work off your infinite guilt through social justice B activism. It inspires self-righteousness. Male and female distinctions are gender constructs, and it seeks to erase those lines because they are oppressive. It celebrates abortion as an expression of female liberation from patriarchal oppression. It excludes from the circle of the oppressed, preborn who are eliminated at a gut-wrenching rate. It is the leading cause of death on the planet. It shrugs its shoulders at that. It does not include and markets itself as being very inclusive. It is very exclusive. It wipes out the smallest among us from the circle of people we should care for.

Zaspel:

Okay, the elevator speech – you have about a minute to explain to someone the message you are trying to get across in your book. What do you say?

Williams:

That justice, if we start with God, if we keep the Gospel first, becomes something beautiful and compelling and redemptive in unifying. If we do not start with God and the Gospel, then we end up with counterfeit justice that is destructive and divisive and hurts the very people we want to help. We will care about the kind of justice that glorifies God first. My friend and mentor John Perkins, who wrote the forward, says, “First start with God, if we don’t start with him first then whatever we are seeking, it ain’t justice. Second, be one in Christ. Christian brothers and sisters, black, white, rich, poor, we are family. If we give a foothold to any kind of tribalism it can tear down that unity and we are not giving God justice. Third, preach the Gospel. The Gospel of Jesus’ incarnation, his perfect life, his death as our substitute, his triumph over sin and death, is good news for everyone. If we replace that Gospel with this or that man-made political agenda, then we ain’t doing biblical justice. Fourth and finally, teach truth. Without truth there can be no justice. What the ultimate standard of truth is not our feelings, not popular opinion, not what presidents, or politicians say. God’s word is the standard of truth. So, if we are trying harder to align with the rising opinions of our day than with the Bible then we ain’t doing real justice.”

Zaspel:

We are talking to Dr. Thaddeus Williams about his new book, Confronting Injustice without Compromising Truth: 12 Questions Christians Should Ask About Social Justice. It is about as contemporary a subject as you could want, and Thaddeus guides us to think through it well.

Thaddeus, thanks for talking to us today.

Williams:

Thanks so much for the great questions. It has been a pleasure.